U.S.A.

Gross returned from the war in a poor psychological condition. Whilst he had been

tempted to return to Paris, he realized that his presence there in the immediate

aftermath of the war would not have been a good idea. His wife, Hildegard Rath,

who was also an artist, decided to emigrate to the USA. Given Gross’s traumatic war

experiences, it was hoped that a totally new environment would speed his

rehabilitation.

1948 Exhibition: Macbeth Gallery

Whilst living mostly in New Hampshire Gross had two major exhibitions at the

Macbeth Gallery in New York. The 1948 exhibition booklet is prefaced with the

following introduction:

“Hermann Gross is one of the many war casualties forced to leave the

scenes of his youth and early manhood to seek refuge in a still free land

where the opportunity is present to work out in his own way long

cherished ideals of Christianity and their application to human conduct.

Always religious in the best sense of the term, the recent world holocaust

has further strengthened his unshakeable belief in the teachings of the

Scriptures as the only true foundation for man’s dealing with man.

To quote his own words:

“Out of the nothing of the devastation of Europe, it seems to me that the

Bible and its message is a salvation. There is nothing which is not

reflected there. Its themes for me are not only effervescent actualities,

they are inexhaustible. Their symbolisms are everlasting and modern in

their significance, and in interpreting them, it is I who stand before my

work as the one who has received. To give form to these everlasting

themes is for me a resurrection.”

The following reviews of his paintings in his two exhibitions in New York show that

Gross was seen as a serious artist:

New York Times, 12 December 1948 :

At Macbeth’s Hermann Gross’s religious imagery in gouache and watercolour, a

cross bred of Blake and Roualt , are deeply imagined and utterly convincing

within the limits of his own quite personal use of medium. And the design also

carries personal conviction.

Art Digest: 15 December 1948

Hermann Gross, in his first showing in the United States at the Macbeth

Gallery, creates an impression of genuine religious fervour. Not only are his

watercolours and drawing concentrated on biblical themes but their content is

unmistakeably inspired and directed by conviction in the message of true

Christianity. Although the songs are not new, they are still sung in this instance

with unrestricted vigour and unrelenting accent on the ethical tones.

New York Herald Tribune: 19 December 1948

Hermann Gross is showing a group of recent watercolours and drawings at the

Macbeth gallery through this month. His watercolours are rather murky and

imbued with a religious if somewhat abstruse air, but they do make a strong

appeal to the emotions, and in “Gesmas — The Malefactor to the Right of Christ

and Crucifixion he has reached his climax. His drawings are heavy but

sometimes come close to profundity, particularly his rendering of The

Malefactor to the Left of Christ.

Art News: December 1948

His work, forbidden and branded as degenerate by the Nazis, has passed through

the crucible of war-torn Europe and shows in a group of forceful, haunting

compositions in watercolour and crayon, the regeneration of deep artistic and

moral convictions. His favourite themes are inspired by the Bible, from which he

extracts images that run the gamut from a powerful expressionism to

geometrically organized abstractions.

The Sun 19 December 1948

The Hermann Gross drawings in the Macbeth Gallery are exceedingly sombre

and somewhat confused but if anybody has a right to be sombre and confused it

is Mr Gross for he is one of the displaced artists from Germany obliged to start a

new career in a new land. He is religious, occupying himself with themes from

many angles but not arriving, on the present occasion, at any very satisfactory

compositions. He has a leaning toward the abstract, and the most moving of his

compositions is the most abstract of all, the one called The Malefactor to the Left

of Christ, and in it there is a shaft of light penetrating the darkness which must

be allowed to be dramatic.

1951 Exhibition: Macbeth Gallery

The New York Times: 26 January 1951

His watercolours now at the Macbeth Gallery use both abstraction and

stylisation as means of expression for his religious subjects. Perhaps his greatest

gift is a mastery of smouldering and effective colour, patches of which get put

together like a fluid changing mosaic. Obviously, a descendant of the German

Expressionists, Gross makes personal use of these idioms. Here is religious

painting in a wholly contemporary mode, weakened neither by sentimentality

nor adherence to worn-out imagery. The implications reach out into twentieth

century living. Curiously, the more abstract of these paintings seem to have the

clearest and most forceful impact.

New York Herald Tribune: 28 January 1951

Of two artists exhibiting figurative work, Hermann Gross at the Macbeth

Gallery is the more dramatic in his paintings of religious subjects. Here, the

atmosphere of the show is heavy with movement, the dark and shattered surfaces

of the canvasses giving impressions reminiscent of Kokoschka and German

Expressionists.

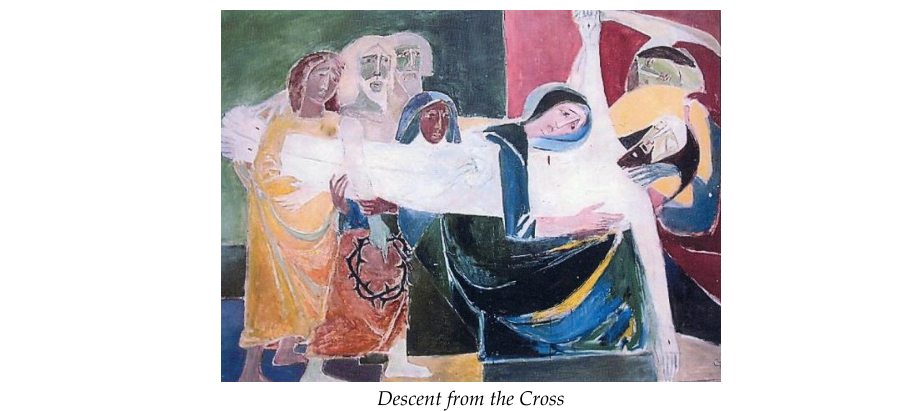

Descent from the Cross was one of the paintings exhibited at the Macbeth Gallery in

1951. Strictly speaking, it should be more properly be titled ‘The Lamentation’, as

most paintings with the title ‘Descent from the Cross’ – Fra Angelico (1437/40), Roger

van der Weyden (1435), Rubens (1612) and Rembrandt (1633).

In Gross’s painting we appear to have the three Marys – the Virgin Mary, Mary

Cleophas and Mary Magdalene – along with Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus.

The crown of thorns, which figures prominently in the painting, is usually linked to

Joseph of Arithmathea who is believed to have brought Christianity to the Britons in

the first century AD.

What is interesting about this painting is that Gross has abandoned the intensely

dark and forbidding depictions of the Crucifixion painted in a style strongly

reminiscent of George Roualt that were produced with obsessive regularity in the

immediate post war years.

During that time Gross was slowly recovering from the acute physical and

psychological trauma he had personally experienced as a conscript in the bloody

military retreat of the German army from the Russian Front in the final stages of

World War Two.

This tempera painting and the way the figures are depicted with great simplicity

owes a clear debt to early Byzantine art. Because tempera paint cannot be applied in

thick layers as oil paints can, they rarely have the deep colour saturation that oil

paintings can achieve. Thus, the colours of an unvarnished tempera painting

resemble a pastel – giving a muted and soft tonality. Traditionally also, in Byzantine

art the human face is portrayed lacking emotion and possessing all the impassiveness

of a mask. It is the spiritual intensity of Byzantine art which enables the viewer to

gain some understanding of the mystery of life. The strong influence of Byzantine art

can also be seen in the work of Gross’s painting teacher in Paris before World War

Two – Picasso.

U.S.A.

Gross returned from the war in a poor

psychological condition. Whilst he had

been tempted to return to Paris, he realized

that his presence there in the immediate

aftermath of the war would not have been

a good idea. His wife, Hildegard Rath,

who was also an artist, decided to emigrate

to the USA. Given Gross’s traumatic war

experiences, it was hoped that a totally

new environment would speed his

rehabilitation.

1948 Exhibition:

Macbeth Gallery

Whilst living mostly in New Hampshire

Gross had two major exhibitions at the

Macbeth Gallery in New York. The 1948

exhibition booklet is prefaced with the

following introduction:

“Hermann Gross is one of the many

war casualties forced to leave the

scenes of his youth and early

manhood to seek refuge in a still free

land where the opportunity is

present to work out in his own way

long cherished ideals of Christianity

and their application to human

conduct. Always religious in the best

sense of the term, the recent world

holocaust has further strengthened

his unshakeable belief in the

teachings of the Scriptures as the

only true foundation for man’s

dealing with man.

To quote his own words:

“Out of the nothing of the

devastation of Europe, it seems to

me that the Bible and its message is

a salvation. There is nothing which

is not reflected there. Its themes for

me are not only effervescent

actualities, they are inexhaustible.

Their symbolisms are everlasting

and modern in their significance,

and in interpreting them, it is I who

stand before my work as the one who

has received. To give form to these

everlasting themes is for me a

resurrection.”

The following reviews of his paintings in

his two exhibitions in New York show that

Gross was seen as a serious artist:

New York Times, 12 December 1948 :

At Macbeth’s Hermann Gross’s

religious imagery in gouache and

watercolour, a cross bred of Blake and

Roualt , are deeply imagined and utterly

convincing within the limits of his own

quite personal use of medium. And the

design also carries personal conviction.

Art Digest: 15 December 1948

Hermann Gross, in his first showing in

the United States at the Macbeth

Gallery, creates an impression of

genuine religious fervour. Not only are

his watercolours and drawing

concentrated on biblical themes but their

content is unmistakeably inspired and

directed by conviction in the message of

true Christianity. Although the songs

are not new, they are still sung in this

instance with unrestricted vigour and

unrelenting accent on the ethical tones.

New York Herald Tribune: 19 December

1948

Hermann Gross is showing a group of

recent watercolours and drawings at the

Macbeth gallery through this month.

His watercolours are rather murky and

imbued with a religious if somewhat

abstruse air, but they do make a strong

appeal to the emotions, and in “Gesmas

— The Malefactor to the Right of Christ

and Crucifixion he has reached his

climax. His drawings are heavy but

sometimes come close to profundity,

particularly his rendering of The

Malefactor to the Left of Christ.

Art News: December 1948

His work, forbidden and branded as

degenerate by the Nazis, has passed

through the crucible of war-torn Europe

and shows in a group of forceful,

haunting compositions in watercolour

and crayon, the regeneration of deep

artistic and moral convictions. His

favourite themes are inspired by the

Bible, from which he extracts images

that run the gamut from a powerful

expressionism to geometrically

organized abstractions.

The Sun 19 December 1948

The Hermann Gross drawings in the

Macbeth Gallery are exceedingly sombre

and somewhat confused but if anybody

has a right to be sombre and confused it

is Mr Gross for he is one of the displaced

artists from Germany obliged to start a

new career in a new land. He is

religious, occupying himself with themes

from many angles but not arriving, on

the present occasion, at any very

satisfactory compositions. He has a

leaning toward the abstract, and the

most moving of his compositions is the

most abstract of all, the one called The

Malefactor to the Left of Christ, and in it

there is a shaft of light penetrating the

darkness which must be allowed to be

dramatic.

1951 Exhibition:

Macbeth Gallery

The New York Times: 26 January 1951

His watercolours now at the Macbeth

Gallery use both abstraction and

stylisation as means of expression for his

religious subjects. Perhaps his greatest

gift is a mastery of smouldering and

effective colour, patches of which get put

together like a fluid changing mosaic.

Obviously, a descendant of the German

Expressionists, Gross makes personal

use of these idioms. Here is religious

painting in a wholly contemporary

mode, weakened neither by

sentimentality nor adherence to worn-

out imagery. The implications reach out

into twentieth century living.

Curiously, the more abstract of these

paintings seem to have the clearest and

most forceful impact.

New York Herald Tribune: 28 January

1951

Of two artists exhibiting figurative

work, Hermann Gross at the Macbeth

Gallery is the more dramatic in his

paintings of religious subjects. Here, the

atmosphere of the show is heavy with

movement, the dark and shattered

surfaces of the canvasses giving

impressions reminiscent of Kokoschka

and German Expressionists.

Descent from the Cross was one of the

paintings exhibited at the Macbeth Gallery

in 1951. Strictly speaking, it should be

more properly be titled ‘The Lamentation’,

as most paintings with the title ‘Descent

from the Cross’ – Fra Angelico (1437/40),

Roger van der Weyden (1435), Rubens

(1612) and Rembrandt (1633).

In Gross’s painting we appear to have the

three Marys – the Virgin Mary, Mary

Cleophas and Mary Magdalene – along

with Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus.

The crown of thorns, which figures

prominently in the painting, is usually

linked to Joseph of Arithmathea who is

believed to have brought Christianity to

the Britons in the first century AD.

What is interesting about this painting is

that Gross has abandoned the intensely

dark and forbidding depictions of the

Crucifixion painted in a style strongly

reminiscent of George Roualt that were

produced with obsessive regularity in the

immediate post war years.

During that time Gross was slowly

recovering from the acute physical and

psychological trauma he had personally

experienced as a conscript in the bloody

military retreat of the German army from

the Russian Front in the final stages of

World War Two.

This tempera painting and the way the

figures are depicted with great simplicity

owes a clear debt to early Byzantine art.

Because tempera paint cannot be applied

in thick layers as oil paints can, they rarely

have the deep colour saturation that oil

paintings can achieve. Thus, the colours of

an unvarnished tempera painting resemble

a pastel – giving a muted and soft tonality.

Traditionally also, in Byzantine art the

human face is portrayed lacking emotion

and possessing all the impassiveness of a

mask. It is the spiritual intensity of

Byzantine art which enables the viewer to

gain some understanding of the mystery of

life. The strong influence of Byzantine art

can also be seen in the work of Gross’s

painting teacher in Paris before World War

Two – Picasso.