World War 2

It is known that when he was stationed in Paris at the beginning of the war Gross

went to see Picasso, with whom he had been a pupil before the war. Gross recalled

that when he entered the studio, he became aware of the fact that he was wearing his

Luftwaffe uniform and apologized to Picasso. However, according to Gross, Picasso

graciously brushed the apology aside and simply said: “I only see the painter in

you.”

In 1940 Gross was called up and served in Luftwaffe Propaganda Kompanie 3 which

had been set up by Hermann Goering and which was stationed in Paris. He was an

Obergefreiter (Royal Air Force equivalent of Leading Aircraftman) and engaged as a

Pressezeichner (press draughtsman).

Such propaganda companies usually consisted of reporters, radio commentators,

photographers, cameramen and artists, whose duty it was to provide reports of

troops in action for publication by press and radio and to take film for inclusion in

newsreels.

Gross’ work in the propaganda unit involved him in a wide variety of activities. One

of the more bizarre tasks he was called upon to undertake was to ‘doctor’

photographs of air battles. Photographs would be cut up and rearranged to show

Hurricanes or Spitfires which had been attacking Messerschmitts or Heinkels being

shown as caught in a hail of imaginary bullets from diving and triumphant

Messerschmitts or Heinkels! These fake pictures had then to be approved by the

propaganda section before being sent to the newspapers for printing. The faking of

the photographs had to be done very speedily so that no-one would suspect the

deception. The German people would then be provided with ‘evidence’ not only of

the supremacy of the Luftwaffe but also the magnificent achievements of

Reichsmarschall Goering, head of the Luftwaffe. The truth was that, during what

later came to be called the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe was sustaining heavy

losses, knowledge of which would certainly have dented national morale.

Members of the Luftwaffe propaganda units were accorded certain privileges that

were denied other servicemen: the most obvious being that they were equipped with

pencils as opposed to rifles and expected to engage in creative as opposed to

destructive work. Such privileges may have represented payment for their silence

because they would be among the few who would have known what was really

happening.

All the drawings undertaken by Gross concerned the defences which were being

constructed along the French coast – Kanalküste. From the topography it is almost

certainly the chalk cliffs somewhere along the Normandy coast that are being shown.

It had been the intention of Hitler’s Wall to reduce German military weakness in the

West and thereby deter or impede an Allied invasion. The Todt Organization, a semi-

independent agency under the Ministry of Armaments, was responsible for the

Wall’s construction. Whilst Hitler boasted that he was the greatest fortress builder of

all time, he never once visited the Channel fortifications.

The intention of the German propaganda machine and presumably the purpose of

Gross’s sketches was to emphasize the impregnability of these fortifications in the

months prior to the D-Day landings. In the event, the Wall proved less effective than

had been promised: it was breached on a single day – 6 June 1944 – by British,

Canadian, and American troops.

The question arises as to whether these carefully drawn sketches are simple and

straightforward representations of what lay before Gross, or instead was he trying to

communicate a hidden message, which if it had been detected would almost

certainly have resulted in harsh punishment – possibly death? If it was the latter

what was it that drove Gross to act in this way? It is doubtful if there was any one

factor. He would have been angered at the dismissal by the Nazis of most of modern

art as ‘degenerate’ – particularly the work of those Jewish artists like Chagall ,

Modigliani , and Soutine who he particularly admired. The wholesale pillaging of the

art treasures of Paris by the Nazis that he witnessed would have depressed him, as

Paris had been his beloved spiritual home.

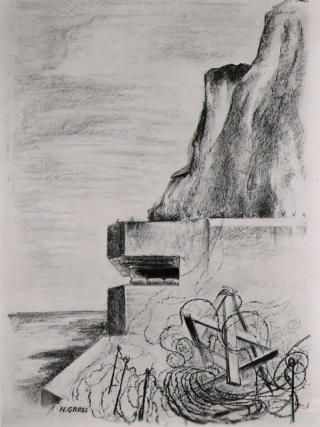

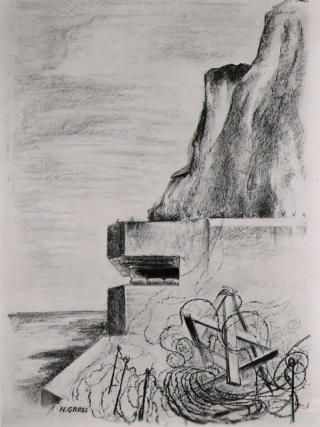

Sketch One

Presumably, the intention in Sketch One is to take the

bunker as the principal focal point, yet it is what lies

beside the bunker that catches our attention. Is it

accidental that in this sketch the discarded planks that

lie alongside the bunker have fallen in the shape of a

cross? At the top of the central plank there is a circle

of barbed wire. Is it far fetched to imagine this as the

crown of thorns on Christ’s brow?

After the war Gross was obsessed with producing an

endless series of dark brooding pictures of the

crucifixion and resurrection. In studying the planks

entangled in the barbed wire, is it also possible to

detect a distorted Star of David swathed in barbed

wire? Might this be an allusion to the internment of Jews and others in concentration

camps?

What else might this sketch be saying? We are presented with a reinforced and

sharply angular concrete building, the simplicity, functionality, and brutality of

which mirror features of Bauhaus architecture. It is ironic that Bauhaus architecture

was discredited by the Nazi regime not least because of its association with the

Weimar Republic. A feature of the bunker itself is that the observation platform is

empty. We have a skull-like construction that is eyeless and lacking vision.

A curious aspect of this sketch is the haphazard way in which the barbed wire lies

alongside the bunker. It seems improbable that any self-respecting German soldier

would have tolerated such an inadequate and untidy defensive structure. One is

tempted to conclude that Gross used artistic licence here to make a point. Whilst the

bunker sketched by Gross gives all the appearance of something solid and

permanent, the chalk cliffs behind it, which Gross highlights, remind us that nothing

is enduring in the face of the sea. And so, it has proved, for most of the 15,000

bunkers and other defensive fortifications built along the Channel coast are in the

process of disintegration, having been affected by erosion and rock falls. Was Gross

implying that tyrannies, like bunkers, do not last forever?

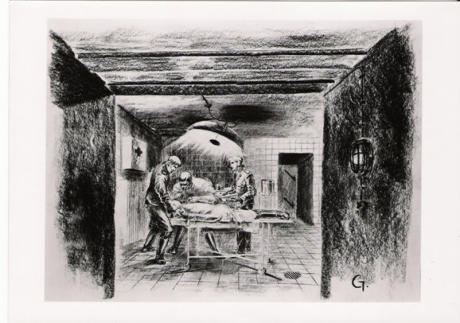

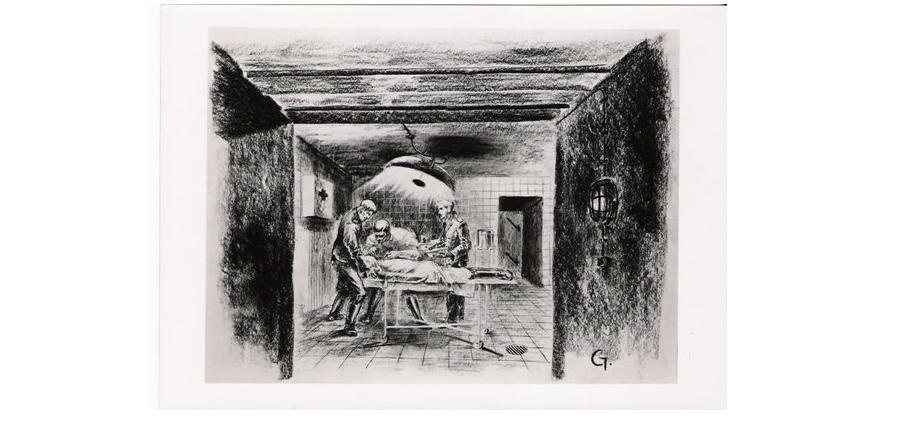

Sketch Two

The meticulously clean, bloodless, and aseptic tiled underground operating theatre in

Sketch Two is striking for several reasons. All the soldiers, including the person who

is being operated upon, are accoutred in incongruously shiny jackboots a symbol

later to be applied to cruel and authoritarian behaviour or rule.

There is a high degree of irony here too in that even jackbooted soldiers are revealed

as vulnerable and require dedicated care and attention to survive.

The operation is conducted adjacent to a cupboard on which there is what one must

assume to be a Red Cross - the symbol that is placed on humanitarian and medical

vehicles and buildings to protect them from military attack!

Whilst there is always a danger of reading too much into a drawing, it is noticeable

that the stability of the trolley upon which this delicate operation is being performed

is dependent on the cross bracing joining the legs. Without such cross bracing the

table would collapse. Put another way, without the cross (i.e., Christianity),

civilization will collapse.

Sketch Three

In Sketch Three it is tempting to see

the three gigantic concrete mixers

that are located at the top of a hill as

a grotesque representation of

Calvary – the site of Christ’s

crucifixion. The paradox here is that

the three mixers are only kept ‘alive’

through the nonstop efforts of slave

labour. We are witnessing a modern

day ‘crucifixion’ in which many of

those working on these sea defences

died. The inference that this sketch

may be an allusion to Calvary is

strengthened by reference to the succession of sketches that Gross drew of crucifixion

scenes after the war.

Was Gross seeking to communicate hidden messages in these sketches? Art in

Northern Europe has been rich in hidden symbolism. For example, in the 15th

century Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden , two masters of Northern

Renaissance art, used symbols to communicate messages which would have been

viewed as heretical and subversive if spoken or written at that time. Through their

art they were able to allude to the kind of shortcomings in the Catholic Church that

Martin Luther later condemned (e.g., van Eyck’s Virgin and Child with Chancellor

Rolin: 1433 Musée du Louvre, Paris and van der Weyden’s The Seven Sacraments:

1445-50 Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp). This was risky because

their livelihood depended to a significant degree on church patronage. They were

taking a gamble just as Gross was doing; however, the stakes for Gross were much

higher, as he was commenting critically not only about the brutal character of the

Nazi regime but also its antipathy to art and religion.

Towards the end of the war, Gross was posted to Poland and Russia, where he served

as a guard for the command headquarters. There he had to endure bitterly cold

winters with inadequate clothing and equipment.

Whether Gross’ subsequent transfer to the Eastern Front stemmed from official

concerns raised by his work as a war artist will never be known. It is more likely that

the transfer was part of a major deployment of military personnel from the Western

to the Eastern Front which was crumbling in the face of the remorseless Russian

advance.

It is not known how he managed to return to Germany after the collapse of the

Eastern Front and the subsequent rout of the German army. However, we do know

that his studio in Landsbergerstrasse, Berlin, was destroyed in an air raid in 1945.

World War 2

It is known that when he was stationed in

Paris at the beginning of the war Gross

went to see Picasso, with whom he had

been a pupil before the war. Gross recalled

that when he entered the studio, he

became aware of the fact that he was

wearing his Luftwaffe uniform and

apologized to Picasso. However, according

to Gross, Picasso graciously brushed the

apology aside and simply said: “I only see

the painter in you.”

In 1940 Gross was called up and served in

Luftwaffe Propaganda Kompanie 3 which

had been set up by Hermann Goering and

which was stationed in Paris. He was an

Obergefreiter (Royal Air Force equivalent

of Leading Aircraftman) and engaged as a

Pressezeichner (press draughtsman).

Such propaganda companies usually

consisted of reporters, radio

commentators, photographers, cameramen

and artists, whose duty it was to provide

reports of troops in action for publication

by press and radio and to take film for

inclusion in newsreels.

Gross’ work in the propaganda unit

involved him in a wide variety of activities.

One of the more bizarre tasks he was

called upon to undertake was to ‘doctor’

photographs of air battles. Photographs

would be cut up and rearranged to show

Hurricanes or Spitfires which had been

attacking Messerschmitts or Heinkels

being shown as caught in a hail of

imaginary bullets from diving and

triumphant Messerschmitts or Heinkels!

These fake pictures had then to be

approved by the propaganda section

before being sent to the newspapers for

printing. The faking of the photographs

had to be done very speedily so that no-

one would suspect the deception. The

German people would then be provided

with ‘evidence’ not only of the supremacy

of the Luftwaffe but also the magnificent

achievements of Reichsmarschall Goering,

head of the Luftwaffe. The truth was that,

during what later came to be called the

Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe was

sustaining heavy losses, knowledge of

which would certainly have dented

national morale.

Members of the Luftwaffe propaganda

units were accorded certain privileges that

were denied other servicemen: the most

obvious being that they were equipped

with pencils as opposed to rifles and

expected to engage in creative as opposed

to destructive work. Such privileges may

have represented payment for their silence

because they would be among the few who

would have known what was really

happening.

All the drawings undertaken by Gross

concerned the defences which were being

constructed along the French coast –

Kanalküste. From the topography it is

almost certainly the chalk cliffs somewhere

along the Normandy coast that are being

shown.

It had been the intention of Hitler’s Wall to

reduce German military weakness in the

West and thereby deter or impede an

Allied invasion. The Todt Organization, a

semi-independent agency under the

Ministry of Armaments, was responsible

for the Wall’s construction. Whilst Hitler

boasted that he was the greatest fortress

builder of all time, he never once visited

the Channel fortifications.

The intention of the German propaganda

machine and presumably the purpose of

Gross’s sketches was to emphasize the

impregnability of these fortifications in the

months prior to the D-Day landings. In the

event, the Wall proved less effective than

had been promised: it was breached on a

single day – 6 June 1944 – by British,

Canadian, and American troops.

The question arises as to whether these

carefully drawn sketches are simple and

straightforward representations of what

lay before Gross, or instead was he trying

to communicate a hidden message, which

if it had been detected would almost

certainly have resulted in harsh

punishment – possibly death? If it was the

latter what was it that drove Gross to act in

this way? It is doubtful if there was any

one factor. He would have been angered at

the dismissal by the Nazis of most of

modern art as ‘degenerate’ – particularly

the work of those Jewish artists like

Chagall , Modigliani , and Soutine who he

particularly admired. The wholesale

pillaging of the art treasures of Paris by the

Nazis that he witnessed would have

depressed him, as Paris had been his

beloved spiritual home.

Sketch One

Presumably, the intention in Sketch One is

to take the bunker as the principal focal

point, yet it is what lies beside the bunker

that catches our attention. Is it accidental

that in this sketch the discarded planks

that lie alongside the bunker have fallen in

the shape of a cross? At the top of the

central plank there is a circle of barbed

wire. Is it far fetched to imagine this as the

crown of thorns on Christ’s brow?

After the war Gross was obsessed with

producing an endless series of dark

brooding pictures of the crucifixion and

resurrection. In studying the planks

entangled in the barbed wire, is it also

possible to detect a distorted Star of David

swathed in barbed wire? Might this be an

allusion to the internment of Jews and

others in concentration camps?

What else might this sketch be saying? We

are presented with a reinforced and

sharply angular concrete building, the

simplicity, functionality, and brutality of

which mirror features of Bauhaus

architecture. It is ironic that Bauhaus

architecture was discredited by the Nazi

regime not least because of its association

with the Weimar Republic. A feature of the

bunker itself is that the observation

platform is empty. We have a skull-like

construction that is eyeless and lacking

vision.

A curious aspect of this sketch is the

haphazard way in which the barbed wire

lies alongside the bunker. It seems

improbable that any self-respecting

German soldier would have tolerated such

an inadequate and untidy defensive

structure. One is tempted to conclude that

Gross used artistic licence here to make a

point. Whilst the bunker sketched by Gross

gives all the appearance of something solid

and permanent, the chalk cliffs behind it,

which Gross highlights, remind us that

nothing is enduring in the face of the sea.

And so, it has proved, for most of the

15,000 bunkers and other defensive

fortifications built along the Channel coast

are in the process of disintegration, having

been affected by erosion and rock falls.

Was Gross implying that tyrannies, like

bunkers, do not last forever?

Sketch Two

The meticulously clean, bloodless, and

aseptic tiled underground operating

theatre in Sketch Two is striking for several

reasons. All the soldiers, including the

person who is being operated upon, are

accoutred in incongruously shiny

jackboots a symbol later to be applied to

cruel and authoritarian behaviour or rule.

There is a high degree of irony here too in

that even jackbooted soldiers are revealed

as vulnerable and require dedicated care

and attention to survive.

The operation is conducted adjacent to a

cupboard on which there is what one must

assume to be a Red Cross - the symbol that

is placed on humanitarian and medical

vehicles and buildings to protect them

from military attack!

Whilst there is always a danger of reading

too much into a drawing, it is noticeable

that the stability of the trolley upon which

this delicate operation is being performed

is dependent on the cross bracing joining

the legs. Without such cross bracing the

table would collapse. Put another way,

without the cross (i.e., Christianity),

civilization will collapse.

Sketch Three

In Sketch Three it is tempting to see the

three gigantic concrete mixers that are

located at the top of a hill as a grotesque

representation of Calvary – the site of

Christ’s crucifixion. The paradox here is

that the three mixers are only kept ‘alive’

through the nonstop efforts of slave

labour. We are witnessing a modern day

‘crucifixion’ in which many of those

working on these sea defences died. The

inference that this sketch may be an

allusion to Calvary is strengthened by

reference to the succession of sketches that

Gross drew of crucifixion scenes after the

war.

Was Gross seeking to communicate hidden

messages in these sketches? Art in

Northern Europe has been rich in hidden

symbolism. For example, in the 15th

century Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der

Weyden , two masters of Northern

Renaissance art, used symbols to

communicate messages which would have

been viewed as heretical and subversive if

spoken or written at that time. Through

their art they were able to allude to the

kind of shortcomings in the Catholic

Church that Martin Luther later

condemned (e.g., van Eyck’s Virgin and

Child with Chancellor Rolin: 1433 Musée

du Louvre, Paris and van der Weyden’s

The Seven Sacraments: 1445-50 Koninklijk

Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp).

This was risky because their livelihood

depended to a significant degree on church

patronage. They were taking a gamble just

as Gross was doing; however, the stakes

for Gross were much higher, as he was

commenting critically not only about the

brutal character of the Nazi regime but

also its antipathy to art and religion.

Towards the end of the war, Gross was

posted to Poland and Russia, where he

served as a guard for the command

headquarters. There he had to endure

bitterly cold winters with inadequate

clothing and equipment.

Whether Gross’ subsequent transfer to the

Eastern Front stemmed from official

concerns raised by his work as a war artist

will never be known. It is more likely that

the transfer was part of a major

deployment of military personnel from the

Western to the Eastern Front which was

crumbling in the face of the remorseless

Russian advance.

It is not known how he managed to return

to Germany after the collapse of the

Eastern Front and the subsequent rout of

the German army. However, we do know

that his studio in Landsbergerstrasse,

Berlin, was destroyed in an air raid in 1945.